ROOM

78

Astronautics

Research Projects Agency (DARPA) in the US and

others have provided project based capital that has

allowed many concepts to be developed from the

bench or lab to proof of concept. From this stage,

companies have much greater success attracting

angel capital and continuing on the capital

lifecycle fly wheel.

Space policy can also be helpful in terms of

protecting intellectual and property rights.

For example, Planetary Resources, a start-up

based in Seattle which is focusing on asteroid

mining was instrumental in helping to pass

the US Space Act of 2015 which provided for

ownership protections of certain space bodies

for commercial use. Other resource oriented

companies, such as Deep Space Industries, have

also been involved with shaping policy regarding

economic rights in space.

The other aspect of policy that drives economics

is certainty. That is to say clarity around what

are the priorities, the funding sources and

the architectures that global sovereign space

programmes are focused on. The more specific,

consistent and long term these priorities are,

the more comfort investors and companies have

regarding their ability to align with them.

Switching from one priority to another or

being vague about what the priorities are has the

opposite effect. For example, it is unclear whether

the new Trump administration will make the Moon

a priority once again. If it does, this could be a

boon to companies such as Astrobotics, Moon

Express and Golden Spike.

I predict that in the future the commercial

sector will take an even larger role in shaping both

the priorities and the laws and policies governing

space. I see this as a consequence of traditional

Traditional space companies

How is the traditional space sector adjusting

to the NewSpace paradigm? Clearly the larger

more established space companies have

competitive advantages. Such companies are

typically large, well-capitalised, with large

amounts of institutional knowledge, talented and

experienced professionals.

However, with that institutionalism comes

perhaps a risk aversion to new ideas and a

classic case of innovator’s dilemma. That

is to say the incentives internally within

traditional space companies reward status quo

behaviour and typically punish disruption. As a

consequence, the inertia of large organisations

leads to incremental improvements in existing

technologies and processes rather than radical

new ways of solving problems.

Another constraint for innovation with many

traditional space companies has been the cost-

plus pricing model. In this model, the company

charges a fee above their cost for delivering the

product or service.

While this has many benefits to the company,

for example consistent and predictable profits,

it provides a disincentive to create new ways

of delivering the product or service that might

reduce its cost or efficiency, since the profits of

the company would also be decreased.

Think of it as runners competing in a race. One

runner is an established athlete and is guaranteed

to always run a five-minute mile, rain or shine,

health or illness. Another set of runners were

literally pulled off the street and start out very

slow, say six minutes or greater. However, there

are hundreds of them and they are all competing

and training every day. Eventually one of those

aspiring runners will overtake the fixed speed

athlete and, since the athlete has not trained

or competed, their ability to then respond

and become more competitive themselves has

atrophied if it ever existed at all.

Impact of space policy

In addition to capital sources, space policy can

have a large impact on industry dynamics and the

economics of space. In recent years, the focus on

using commercial elements for sovereign space

programmes has created large blocks of capital

that have allowed companies such as SpaceX to

flourish and provided credible long term business

plans that have attracted early stage capital for

company formations.

In addition, early stage contract awards by

organisations such as NASA, the Defense Advanced

In addition

to capital

sources,

space policy

can have a

large impact

on industry

dynamics and

the economics

of space

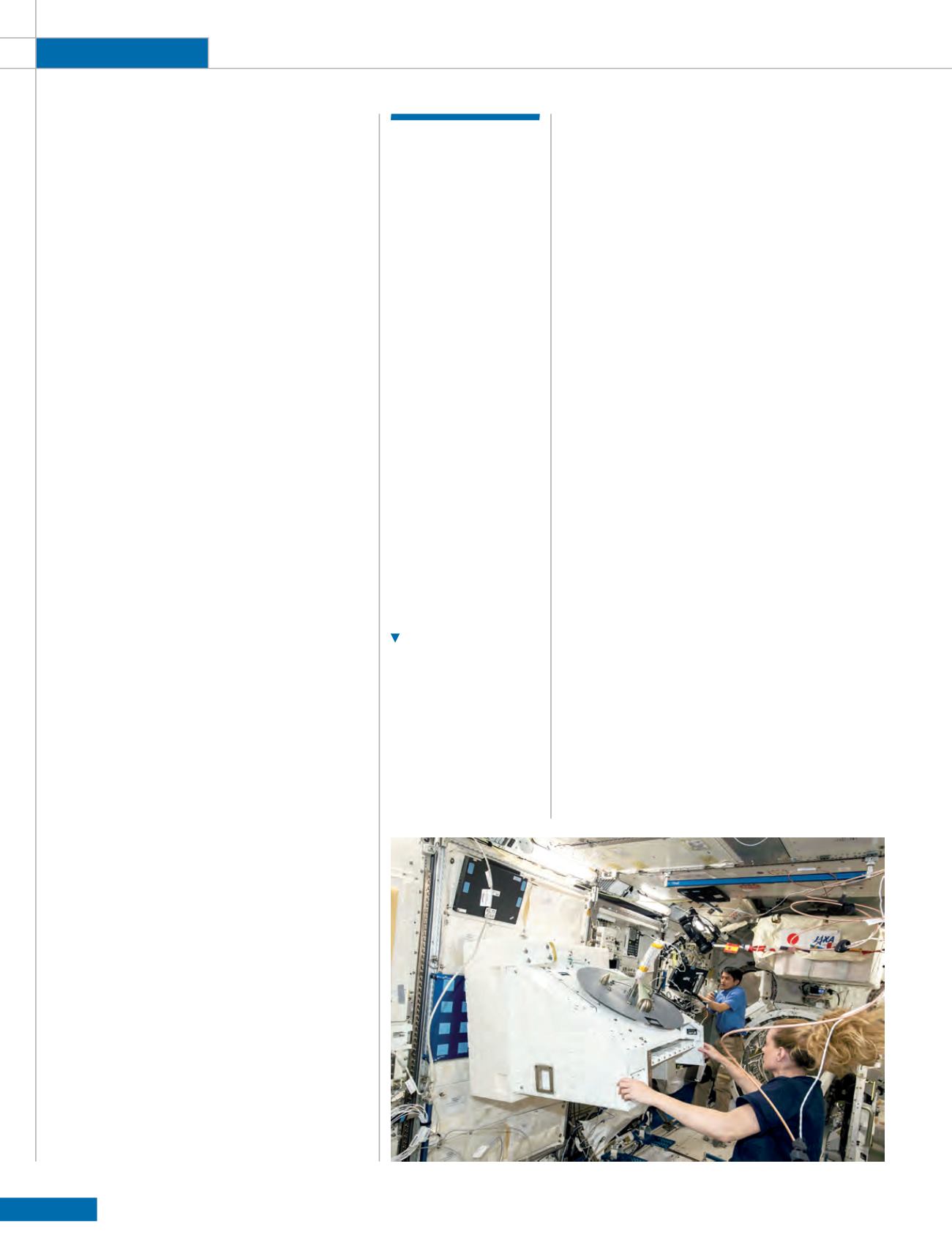

Installation in August

2016 of the NanoRacks

External Platform on the

International Space

Station (ISS). Houston-

based NanoRacks was

formed in 2009 to provide

commercial hardware

and services for the US

laboratory on the ISS via

a Space Act Agreement

with NASA.

NanoRacks