ROOM

69

Astronautics

human lifetime, gathering data well beyond human

sensing capabilities, computing faster and more

precisely than the brain, and ruling operations

with a far greater precision.

Several high-profile space projects have made

headlines in the last years. Behind the scenes, and

essential to the success of any of these endeavours,

is the meaningful integration of technical and non-

technical aspects in design and operation.

Humans should always be at the centre of

any future advanced systems designed for

space exploration, managing the system and

increasing its resilience, such as developing an

industrial technology base for the automation and

remote control of space based operations using

Automated-Human-Robot-System.

Indeed, humans should always be allowed to

decide and act when faced with the unplanned,

the unknown, the risks and the contingencies,

and to evaluate the mission results achieved.

Humans should be considered the strongest link

and systems should be designed around them for

future scenarios.

The challenge of integrating automation and

the human element is not limited to the arena

of Space. Other domains - aviation, the nuclear

industry and maritime search and rescue - share

similar challenges and opportunities in respect

of the human element; how to implement it in

training initiatives, how to engineer the human

element and how to regulate it in design aspects.

The involvement of industry will be increasingly

more important as humans learn to work in

tandem with robots.

Author credits

Thanks for contributions on the article to R. Peldszus, formerly Internal

Research Fellow at ESA-ESOC, Special Studies & Projects, L. Bianchi,

Head of Dependability and Safety Assurance Section at ESA-ESTEC and

M. Gabel, Training and Simluations Coordinator at ESA-ESOC.

Accelerating pace

In today’s world, automation is usually

implemented to achieve lower costs and a

reduction of human error. But automation may

have its downsides too.

Where control centre operators are in the role

of supervisor, automation will be an increasingly

important factor. Systems operators and system

developers will need to work together from the

start, right across the life cycle of the system.

This process will actually move the risk of human

error from ‘operation’ to ‘design’ within the

life cycle. Automated control centres will also

require operators to have more training and more

knowledge management.

The evolution of automation and the pace of its

introduction into everyday life is astonishing. The

use of an autopilot on airplanes has been the norm

and not the exception for many years. Automatic

rail systems are already a reality in many cities and

within a decade we may not need to ‘drive’ a car

any more, beyond indicating the destination.

In this context, the push to increase automation

in space exploration is understandable but

we need to understand our motivation before

embarking on wholesale robotic innovation. Is

replacing all human positions in systems with

automated functions in order to remove the

human error liability possible or desirable?

And although replacing astronauts with robots

might reduce the inconvenience and costs of the

necessary life sustainment functions required in

manned spacecraft, would that actually further the

progress and quality of space exploration?

Augmenting performance

In Earth observation most processes for

establishing and maintaining contact between

the ground station and spacecraft e.g. to

uplink commands or downlink telemetry,

are now automated through schedules and

configuration scripts. There are less routine

activities to be performed by the ground station

controllers, allowing them to concentrate on

more critical activities.

Robotic automation is not just about

the potential to replace human roles and

functions; it also has great potential to

augment human performance.

Automated functions implementation, robots,

drones etc. should be seen as extensions of human

capabilities allowing us to go further in exploring

deep space and planets where environmental

conditions are prohibitive for human life,

attempting missions that could last longer than a

Robotic

automation is

not just about

the potential

to replace

human roles

and functions

- it also has

great potential

to augment

human

performance

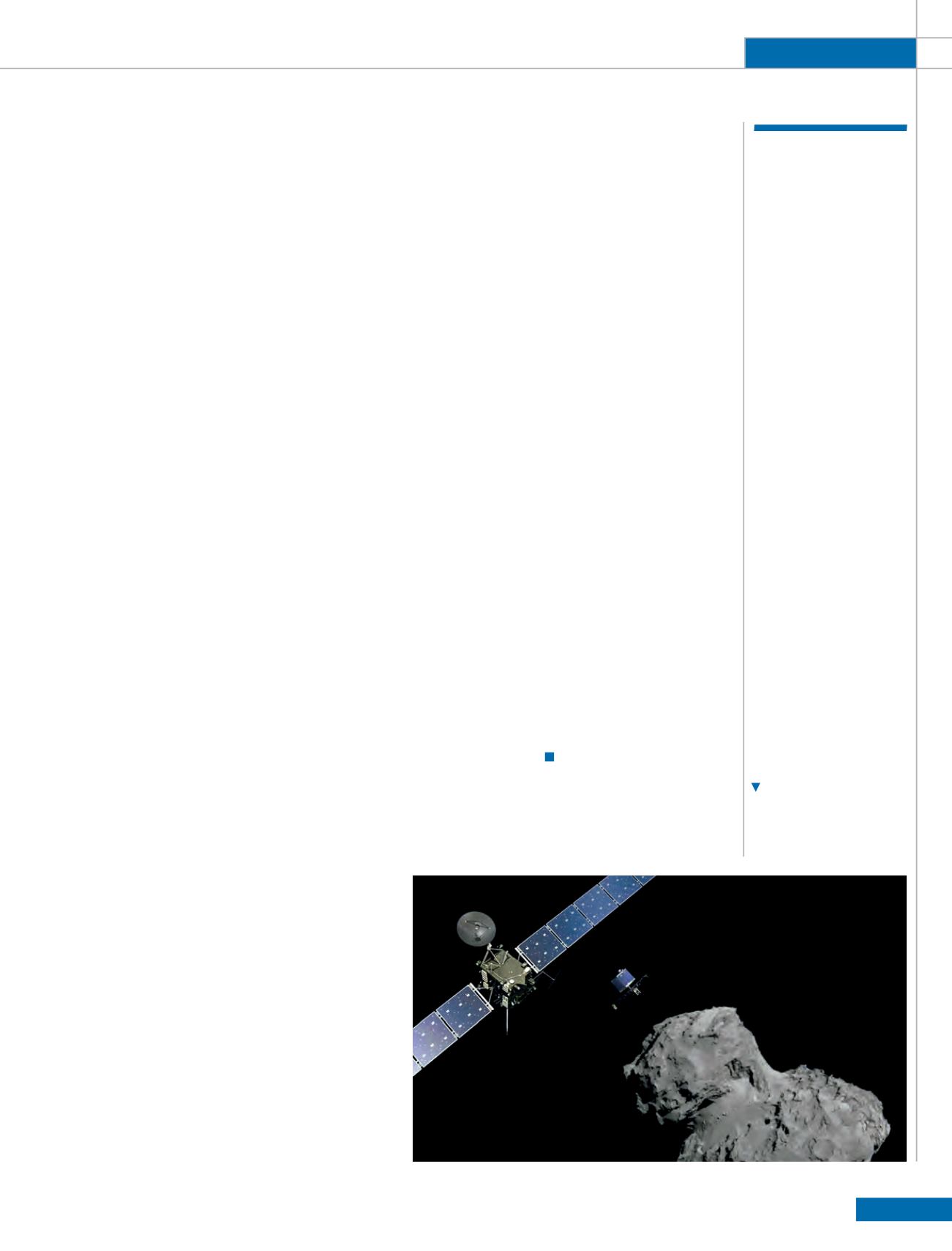

ESA’s Rosetta showing

the deployment of the

Philae lander to comet

67P/Churyumov–

Gerasimenko.