ROOM

19

Special Report

compact radioisotope power system, deep space

nanosats heading out to Jupiter and beyond

will have to rely on their host spacecraft to get

to their destination, run on energy stored in

batteries after their release from their storage/

hibernation container, and relay data back to

Earth through the primary spacecraft.

It is common enough for deep space missions to

use a gravity assist manoeuvre at Venus to provide

a boost in velocity to propel them on their way

to their primary mission target. NASA missions

that have used this slingshot effect include Galileo

(Jupiter), MESSENGER (Mercury), Cassini (Saturn),

and Parker Solar Probe (the Sun). Now, imagine that

every time a mission executes a gravity assist at

Venus, it drops off a small nanosat probe that could

sample and analyse part of Venus’ atmosphere,

relaying the data back to Earth via the vehicle

that dropped it off, or be captured into a stable

orbit that allows longer-term study of our nearest

neighbour. Straight shot, independent trajectories

to Venus are also possible for nanosats.

The Moon is an attractive destination

for nanosats, since it is so close to home,

N

ASA’s Curiosity rover, currently exploring

the Gale crater on Mars, weighs in at

899 kg and the Europa Clipper

spacecraft will probably tip the scales at

over three tonnes. Mass generally drives the cost

of each mission – so bigger spacecraft usually

cost significantly more than smaller ones.

At the other end of the scale in both size and

cost, cubesats and nanosats could, in theory,

fly more missions for the same budget. But

could smaller spacecraft deliver in the space

science arena? The answer, as suggested by a

recent National Academy of Sciences report is a

qualified ‘yes’: small spacecraft such as cubesats

can take on unique science missions but are not

a substitute for the larger ‘flagship’ missions like

Curiosity or Europa Clipper.

Destinations

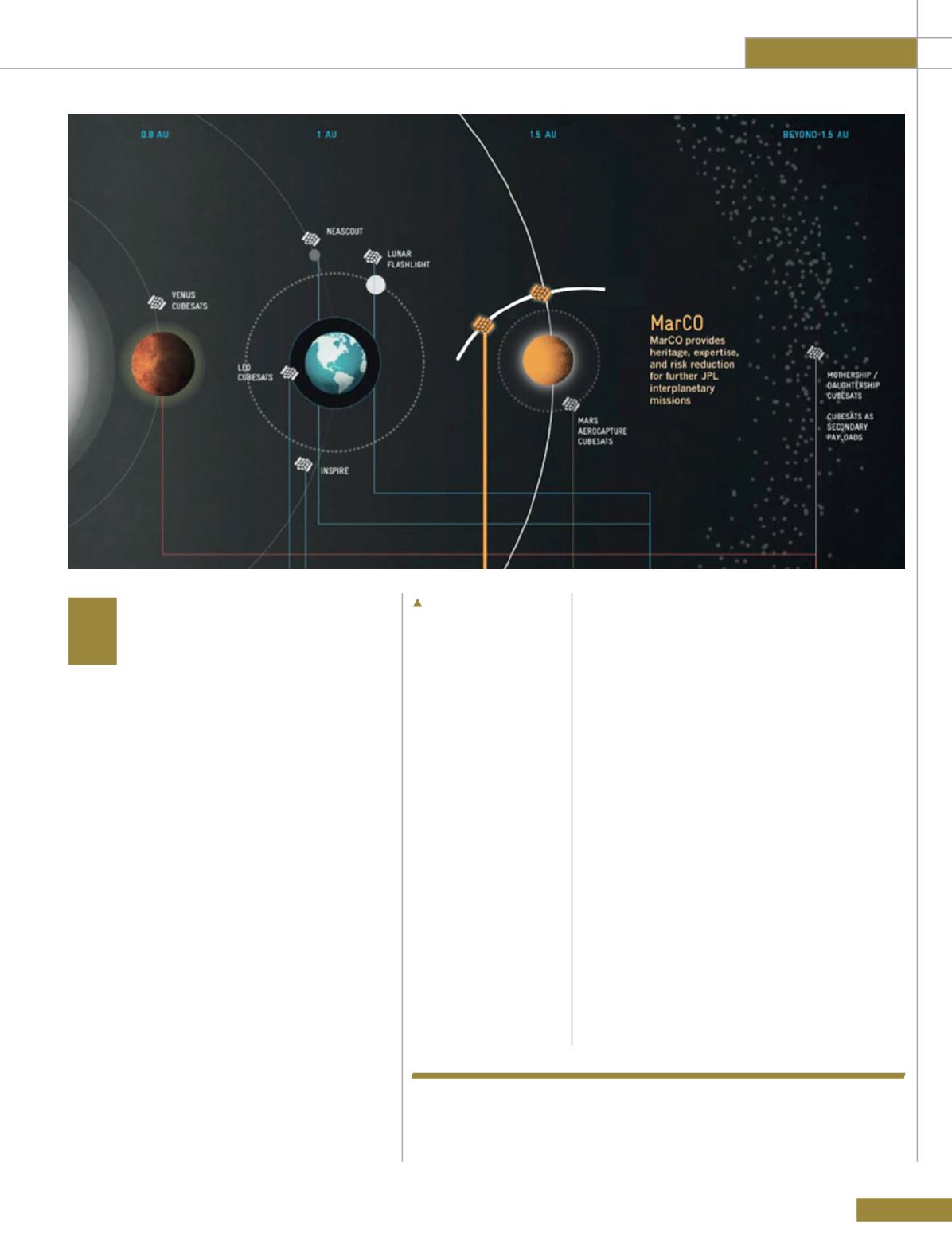

So where can we reasonably expect to explore

in our Solar System with smaller spacecraft?

The Sun is an obvious target, since we can

cost-effectively send cubesats and nanosats

to places that provide a unique vantage point

to view solar phenomena. The inner solar

system is fairly easy to reach, being accessible

to both free-flying and ‘hitch-hiker’ cubesats/

nanosats, while the outer solar system is

currently compatible with just hitching a ride

on a larger spacecraft. Without a suitable,

Exploring our Solar

System with cubesats

and nanosats.

The ‘cubesat kitchen cabinet’ has helped to

conceive some new, exciting science missions

using deep space cubesats and nanosats

NASA/JPL