ROOM

91

Opinion

envoys of almost all humankind. And all speak

fervently of peace.

On 16 July 1969 a Saturn V rocket lifted off on

a historic voyage and four days later millions of

people watched as the first human footprints

were set on the Moon’s desolate surface and a flag

was planted. Though no claim of sovereignty was

made, the familiar stars and stripes is prominent in

many iconic photos of the first lunar landing and

the five that followed.

If any fragments of the flags have survived the

harsh lunar environment, they are most likely by

now bleached of all colour and a ghostly reminder

of an achievement that belongs to all humanity.

In contrast so much else from those first landings

will be very well-preserved. Without wind, water

or weather to erode the soil, equipment, including

cameras and even urine bags, the medals, the olive

branch, the disc and footprints are likely to remain

close to their original state. Imagine if these first

off-world footprints, preserved until now by the

vacuum of space, were erased?

Each of the six crewed lunar landings to date

- all part of NASA’s Apollo programme - was

fraught with its own dramatic missteps and

failures, each representing a litany of firsts and

each reverberating with demonstrations of human

perseverance, ingenuity and accomplishment.

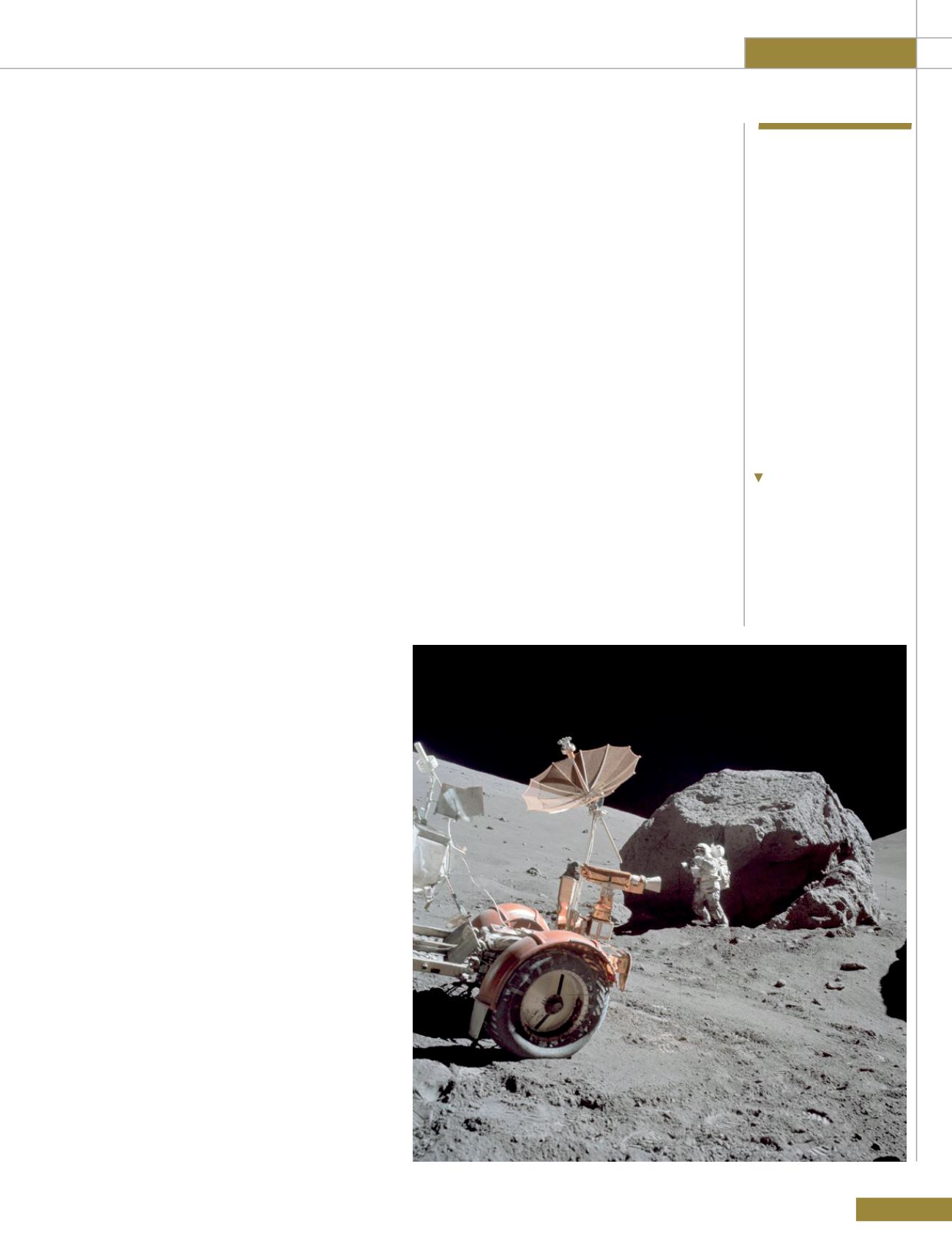

In 1972, Apollo 17 was the final mission and

remains the last time humans travelled beyond

low Earth orbit (LEO). But that will soon change

because it is clear that we stand on the threshold

of the spacefaring age and that our Moon is about

to get very crowded.

Japan, China, Russia and the United States all are

weighing manned Moon missions within the next

decade. Private manned missions may get there

even sooner and more robots will be deployed to

the Moon by nations and private interests from as

early as next year.

It is not difficult to imagine the damage an

autonomous vehicle or an errant astronaut -

an explorer, colonist or tourist - could do to

one of the Apollo lunar landing sites, whether

intentionally or unintentionally.

In 2013, two well-meaning but woefully

misinformed legislators from the United States

sought to have the US Department of Interior

administer the Apollo lunar landing sites as US

National Historic Parks. The resulting Apollo Lunar

Landing Legacy Act of 2013 was ill-conceived and

in violation of United States Treaty obligations and

this attempt to bring the landing sites under the

purview of the United States was roundly, soundly

and rightfully criticised.

First, as George Robinson, retired Associate General

Counsel for the Smithsonian Institution pointed out,

the Act implied that only the United States should be

recognised for the Apollo programme, and yet “many

countries offered and provided critical components

of the programme, from alternate emergency

landing sites, to unique technology and personnel

with equally as unique specialty capabilities, to

tracking stations and on and on.””. And second, it

also implied that the United States has the ability

to make sovereign proclamations in respect of the

Moon which is categorically incorrect and a violation

of international law and the Outer Space Treaty by

which the United States is bound.

Article II of the Treaty states that “outer space,

including the Moon and other celestial bodies,

is not subject to national appropriation by claim

of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation

or by any other means.” It is a principal so

embedded in the bedrock of space exploration as

to be considered by many to be not just a treaty

obligation but customary international law.

With this in mind, For All Moonkind, Inc - a

non-profit organisation seeking to preserve the

memory of all those who toiled during the intense

competition of a Cold War that saw humankind

leap into space - believes it is not the United States,

It is not difficult

to imagine the

damage an

autonomous

vehicle or

an errant

astronaut could

do to one of the

Apollo lunar

landing sites

Astronaut Harrison

Schmitt, a geologist and

the first person initially

trained as a scientist to

walk on the Moon,

photographed on 13

December 1972 during the

third Apollo 17 EVA at the

Taurus-Littrow landing

site.