ROOM

78

Space Science

as fine as 1 Hz - and hunt for signals using these

instruments on existing radio telescopes. The

search strategy was two-pronged: to scan the

entire visible sky at relatively low sensitivity, and

to zero in for a more intensive examination of

approximately 1,000 nearby star systems. Although

the programme cost less than 0.1 percent of

the NASA budget, this effort was killed by the

US Congress a year after observations began,

ostensibly for reasons of economy.

Since then, experiments have continued

primarily at the SETI Institute in the Silicon

Valley and at the University of California Berkeley.

Funding has been via private donations, and the

combined annual effort runs at approximately

three percent of the cost of a single Ariane 5

launch. It is also worth noting that, at present,

only the United States has any dedicated SETI

programmes. Despite the seductive excitement of

proving that there are other beings in the cosmos,

the actual effort to do so has been disappointingly

limited. That, however, may change.

New approaches

Today, there is increased enthusiasm for SETI.

While this is partially due to the surge in

planetary discovery, there are also improvements

in technology that can broaden the search and

increase its speed.

Larger radio telescopes, including the new FAST

500 m radio telescope in China and the Square

Kilometre Array being built in South Africa and

Australia, will increase our sensitivity to signals.

In addition, the unremitting march of digital

technology has allowed more of the radio

spectrum to be sampled in a given amount of

time. For radio telescope arrays, additional

computational power can be used to ‘look’ at

several patches of sky simultaneously. And the

emergence of machine learning is offering the

opportunity to hunt for an unlimited number of

signal types. Past experiments could recognise

only a few.

These improvements are seldom appreciated

by the general public, which imagines SETI as it is

portrayed in the movies. In the Hollywood version,

a lone researcher with headphones strains to hear

anything vaguely odd. That depiction was never

‘true’; computers long ago took over the ‘listening’.

And computers are much better listeners – they

can find weaker signals and check out more of

the radio spectrum. Indeed, because of the rapid

improvement in the speed of computers, it should

be possible to examine approximately a million

star systems for artificial signals in the next two

decades. That’s two to three orders of magnitude

more than were targeted during the first half-

century of SETI.

California’s SETI Institute is getting a head start

on these far larger cosmic surveys by conducting

a programme using its own instrument, the Allen

Telescope Array. The array will observe 20,000 red

dwarf star system over a small number of selected

frequency ranges in the next two years.

Red dwarfs – stars that are both smaller and

dimmer than the Sun – were traditionally of

little interest to SETI researchers. They aren’t

like the Sun, the only star known to harbour a

world with intelligence. But recent exoplanet

studies have shown that a considerable fraction of

these bantam suns have planets in the so-called

‘habitable zone’ – an orbital distance at which

temperatures could be suitable for liquid-water

oceans. Red dwarfs also have the advantage of

enjoying extremely long lifetimes – 10 times that

of a Sun-like star. So, on average, they are several

billions of years older. That is an obvious plus point

when looking for intelligent life, which on Earth

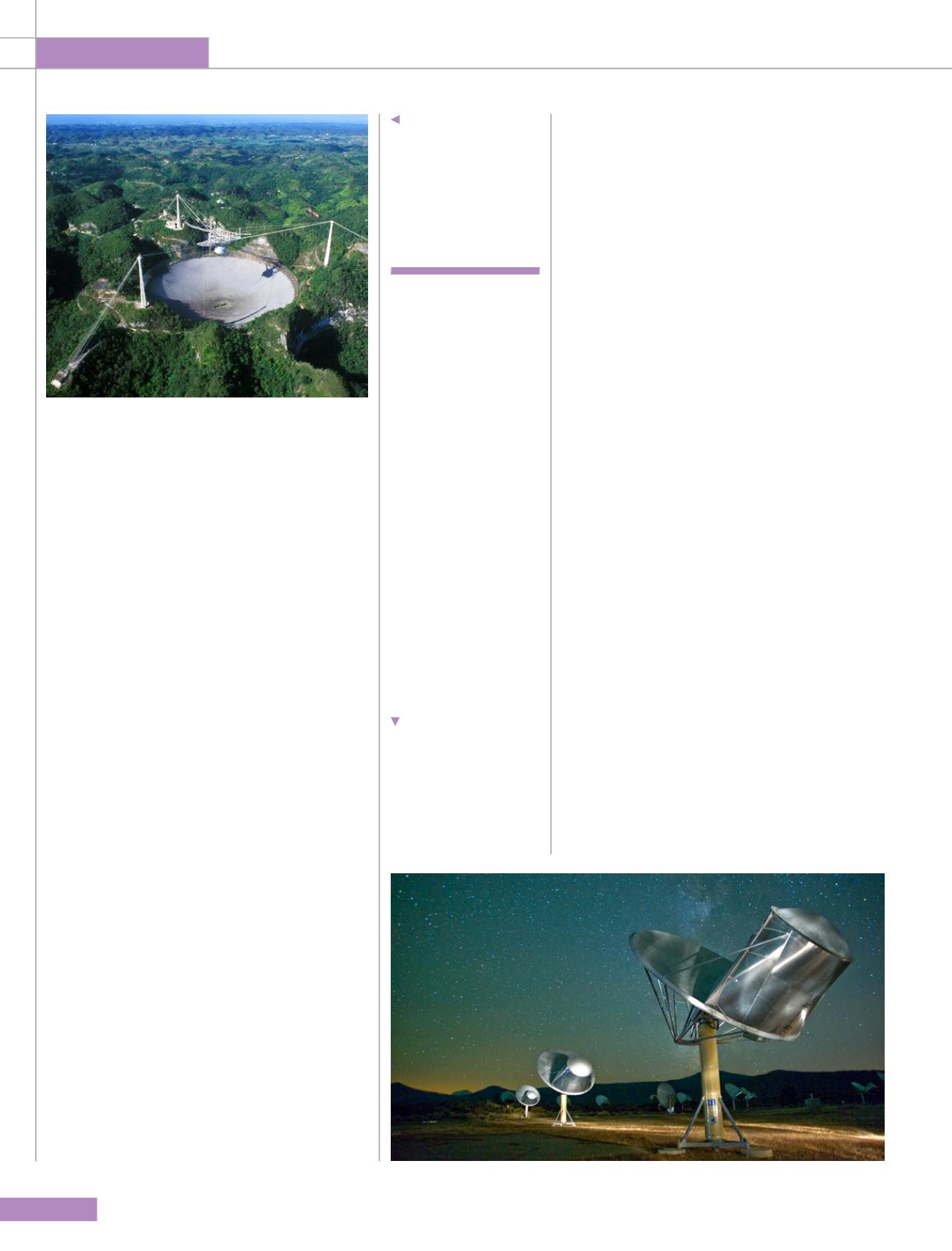

The Allen Telescope

Array (ATA) is a ‘Large

Number of Small Dishes’

(LNSD) array designed to

be highly effective for

simultaneous surveys

undertaken for SETI

projects at centimetre

wavelengths.

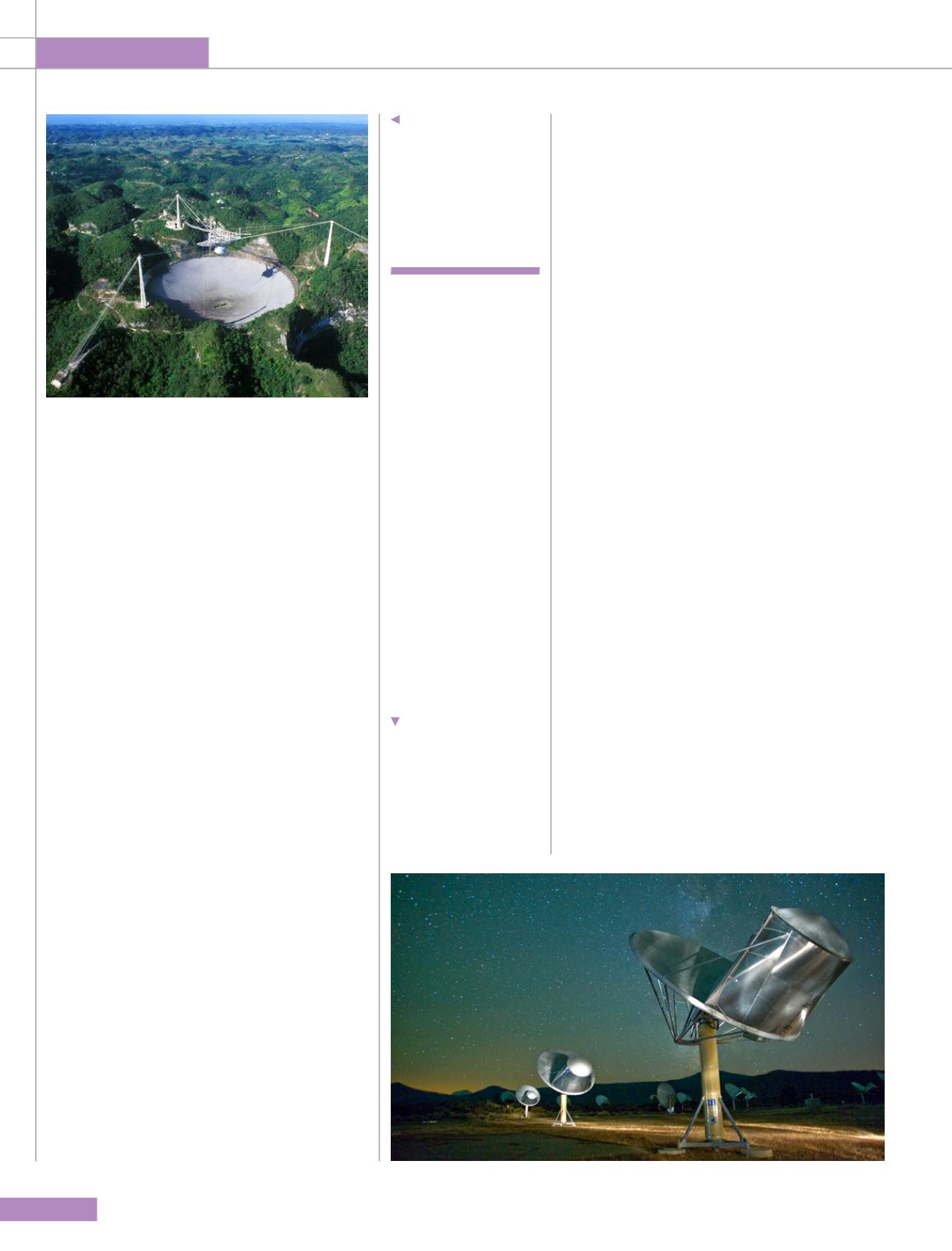

The Arecibo

Observatory radio

telescope in Puerto Rico

has been used for SETI

work many times.

The rapid

improvement

in computer

speed means

it should

be possible

to examine

around a

million star

systems for

artificial

signals in

the next two

decades