ROOM

49

Astronautics

First attempts

By the time the spaceflight era really got under

way there was already a clear understanding of

the potential role of plants in space exploration.

But unlike Tsiolkovsky, modern scientists had

doubts that plants would be able to successfully

grow and reproduce in a zero gravity because their

dependence on gravity was considered too great.

Early experiments also suggested it was unlikely

that plants would thrive in space. From 1971 to 1990

plants in space were cultivated in small greenhouses,

fitted with low-power lights and, for the most part,

without regulatory control systems. Because of the

imperfect horticultural equipment used many of

these experiments failed.

The best result of that period was the successful

growth of arabidopsis (a member of the mustard

family) seeds on the Saylut-7 orbital station in a

Phiton-3 apparatus in 1982. But many later attempts

to repeat this experiment failed.

The Svet greenhouse, a joint project by Russia

and Bulgaria, was the first automated greenhouse

in orbit. It had a larger planting area than previous

devices, a higher vegetation chamber, a much

brighter light system and automatic controls - and it

was also able to process and send to Earth collected

data on the plants’ environment and the conditions

of the greenhouse modules.

In 1990, the first experiment in cultivating pak

choi cabbage and radishes was conducted in

the Svet greenhouse on board the International

Space Station (ISS). The productivity and speed of

ontogenetic plant development (from the earliest

stage to maturity) in this experiment was lower than

in the Earth control group, which again confirmed

the position of those scientists who believed that

weightlessness had a negative impact on plants.

Later, specialists at the Institute of Medical and

Biological Problems (IMBP) at the Russian Academy

of Sciences and the Space Dynamics Laboratory

at Utah State University equipped the Svet

greenhouse with the Gas Exchange Measurement

System (GEMS), which measured hydrocontent

dynamics in the vegetation chamber and plant gas

exchange, as well as controlling the conditions of

plant cultivations.

After in-flight experiments were completed,

control experiments were run on Earth in special

climate-controlled chambers with simulated

dynamics of the main parameters of plant

cultivation, as recorded during the spaceflight. To

provide normal growth and development of plants in

weightlessness, both the correct methodology and

the right equipment to regulate the water and air

settings of the root environment were needed.

The thermo-impulse method of monitoring the

root moisture levels in weightlessness was suggested

and subsequently used, and data obtained on root

moisture levels during these space experiments

provided the necessary information to allow

astronauts to control moisture for the first time in

human spaceflight history.

If at first you don’t succeed…

In 1995 a joint team of Russian and American

researchers attempted to grow super-dwarf wheat in

space for one ontogenesis cycle – ‘from seed to seed’

– in the Svet greenhouse on the Russian Mir space

station. This first attempt was not fully successful;

lamp sets failed and the plants did not form a head,

remaining at the vegetative stage of development. In

Pea flowers in the

‘Lada’ greenhouse.

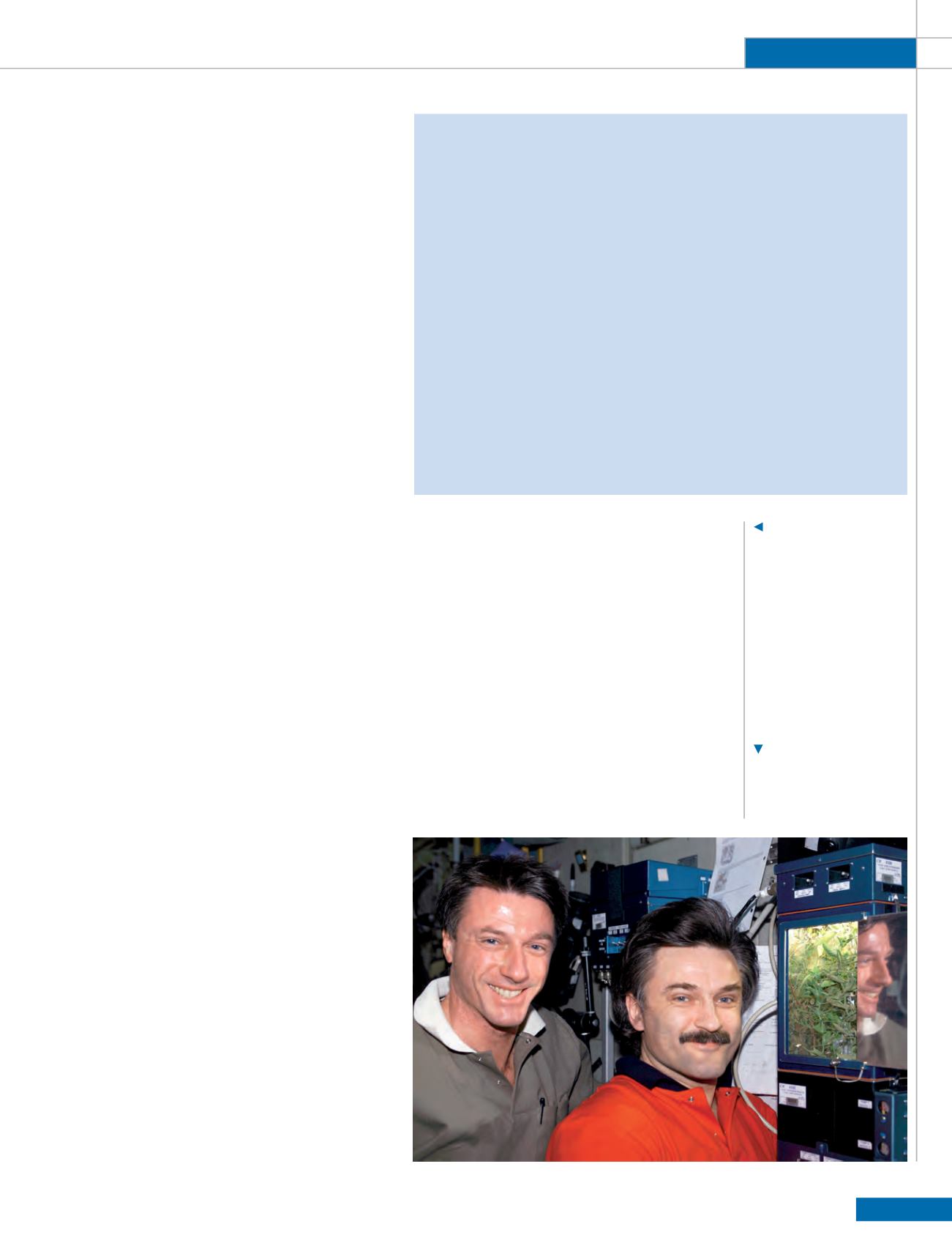

Michael Foale and

Alexander Kaleri beside

the pea plants growing in

the Lada-4 greenhouse

experiment.

FEEL-GOOD FACTOR

The 1997 Brassica rapa L. experiment was noteworthy not only because of

interesting biological results but also because of the intricate work performed

by astronaut Michael Foale on the manual cross pollination of the tiny Brassica

flowers, all achieved despite the dramatic events of 25 June 1997 when Mir was

depressurised after a collision with a Progress transport ship during a docking

test, which almost cost the crewmembers their lives.

In an interview about his in-flight experiment Michael Foale spoke of the wider

benefits he experienced of the presence of green plants.

“The greenhouse experiment provided me with peace of mind,” he said. “It’s a

special sort of task – to be a gardener, to live together with your plants, to fully

grasp their situation and have a sort of connection with them; it impresses on

you visually and allows you to do the sort of work that’s very different from the

extremely technological environment of spaceflight that lacks so many things.

“It’s a connection with Earth that you take with you and that gives you comfort.

I took great pleasure in checking up on the greenhouse every morning. It was

supposed to take twenty minutes a day, but I spent a lot of time in the greenhouse

and valued that time very much. And I think that during lengthy flights or at any

space station, experiments where something is grown [such as plants] can find a

wide range of uses not only in scientific research but also for psychological support.”

Observations like these - on the psycho-emotional condition of space crews - have

been expressed by almost all astronauts that have participated in plant experiments.

NASA